Multiple Relationships and Power in Biblical Counselling

Kenny Larsen

Note: This was originally delivered as a discussion paper for the BCUK roundtable in May 2025.

1. Blurred Lines and Real Relationships

“I’ve known Anna for about a decade, initially as a small group member, then a friend, now as friend and pastor. We have walked a long road together wrestling, amongst other things, with singleness, long term suffering, sexual assault and miscarriages. We’ve also rejoiced over healing, marriage, Christian growth and God’s faithfulness. We have lived in the same house for a while, been on holiday once as families together. Finally, I also met with Anna to do some biblical counselling for almost a year….”

“Matt was the associate pastor of the church I used to attend and my line-manager when I was a ministry trainee there. Through working together, we became friends. Matt recently joined our church, I’m his small group leader and pastor. The roles now seem reversed. Our wives work in similar fields and have a good friendship and his wife, being more senior, has been a significant source of encouragement and support to my wife. I’ve recently started doing some biblical counselling with Matt to address some past issues…"

These kinds of overlapping relationships are normal in church life. If I simply said, “I’ve been catching up with X regularly to work through some hard things they’ve experienced,” no one would blink.

But as soon as we label it “biblical counselling,” questions are raised:

- Is this appropriate?

- Is it ethical?

- Am I too close?

- Should someone else do it?

These questions come about because of our instinctive tendency to see biblical counselling as a branch, or offshoot, of secular counselling.

2. A Secular Backdrop

The Professional Model

Most modern secular ethical codes largely warn against multiple relationships (see appendix). That said, some have softened over the years and there is an increasing recognition that some forms of interaction outside of the strict counsellor-patient model can be beneficial. However, the predominant view strongly resists multiple relationships.

Reasons for this caution include:

- Risk of exploitation from power imbalance

- Impaired objectivity or judgement

- Blurred boundaries and unclear expectations

This is influenced by:

- The medical model of care (clinician–patient distance)

- A history of complex relationships from the early days of psychotherapy.

- In the early days of therapy it was commonplace for therapists to have all manner of relationships with their counselees. It was not unusual to provide therapy for family members, friends, colleagues etc. Freud gave gifts to counselees, analysed his own daughter, arranged a romantic relationship between two counselees. One of Jung’s counselees became his student, colleague and ultimately lover. These things were not unusual. Today they would be seen as clear abuses of power.

Of these the power-imbalance created by a counselling relationship is key. Abigail Shrier writes in her book:1

As psychologist and author Lori Gottlieb explains, “The relationship in the therapy room needs to be its own, distinct and apart,” she writes. “To avoid an ethical breach known as a dual relationship, I can’t treat or receive treatment from any person in my orbit - not a parent of a kid in my son’s class, not the sister of coworkers, not a friend’s mom, not my neighbor.” This ethical guardrail exists to protect a patient from exploitation. A patient may reveal her deepest secrets and vulnerabilities to her therapist. Anyone possessing this much knowledge of a patient’s private life may be tempted to exert undue power. And so the profession makes “dual relationships” off limits.

The secular counselling model sees a real and genuine risk that power can be and is abused within counselling relationships. It seeks to minimise this potential harm by restricting the place where that power can be exercised to the therapy room.

Our issue is two-fold. The risk that the secular models recognises is real - there is a significant power imbalance in these kinds of relationships and it can be abused. But church life and the descriptions of the relationships we are to have with one another is almost the opposite of the medical clinician-patient model.

In church life:

- Relationships are intertwined.

- Counselling happens not in isolation, but in the context of:

- Friendship

- Fellowship

- Shared ministry

- In many settings (especially smaller churches) multiple roles are inevitable unless all care is outsourced.

- Counselling often emerges naturally from existing relationships, not from formal referrals or clinical assessment. It’s the secondary (or third, fourth etc.) relationship.

Therefore, the strict rejection of dual-relationships appears to be an untenable solution within a biblical counselling framework. The medical model is, therefore, almost certainly not the correct starting place for considering how we address power imbalances within biblical counselling relationships. I want to suggest a better approach is to assume the biblical model for our relationships and then consider how to mitigate the risks recognized by secular models so that the way we care for one another is wise and godly.

Initially we’ll sketch a biblical framework, then explore the benefits this brings to counselling, before addressing the challenges more broadly and finally focussing on the issue of power specifically.

3. A Biblical Framework

Who Are We?

The bible uses various metaphors to describe the primary relationships between us:

- body (1 Cor. 12) - connected together, different roles, interdependent

- temple (1 Peter 2:4-5) - equality, worship, common purpose

- flock - (1 Peter 5:1-5) - humility, with role and age distinctions

- family - (pretty much every NT letter, Mark 3:34-35) relational, united, unbreakable bond.

These lead to particular ways we’re to interact with one another, for example:

- We’re able to instruct/ counsel one another as brothers and sisters. (Romans 15:14)

- We should restore one another gently; bearing one another’s burdens. (Galatians 6:1-2)

- As part of the body we’re to speak the truth in love to one another to help the body grow. (Ephesians 4:15-16)

- We’re to confess our sins to one another, pray for one another, and seek those who are wandering away from Christ. (James 5:16,19-20)

These are the forms and implications of relationships that God has caused to exist. We will always be brothers and sisters in God’s family, stones in His temple, members of His body, joined together. Other forms of relationship we create can only happen within these broader and more fundamental categories. Other forms of relationship might give particular shape to these but they cannot be distinct.

For example, all Christians are children of God by his will and through faith in Jesus:

But to all who did receive him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God, who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God. (Jn 1:12–13, ESV)

This concept becomes the basis for the brothers and sisters language in the New Testament (see, for example, Romans 8:9-17) and is true of all believers. However, on top of this fundamental relationship, other temporal relationships can be constructed. For example, a marriage creates a particular temporal relationship within the context of being brother and sister in Christ. Marriage neither removes the sibling relationship (which will continue once the marriage has ceased) nor eclipses it in terms of importance. The same can be said of other relationships between Christians, they exist within the scope of the general relationships God has caused to exist.

Biblical counselling is one such relationship that can be created within this wider framework.

Historical Precedent

It’s worth mentioning that the church has often combined a counselling role with many others. Multiple relationships have been common, even if the terminology used was different. This is easier to see in the multiple roles of the pastor, because it has been written about more extensively.

- Puritans, especially Richard Baxter, saw the pastor-counsellor role as essential. Baxter insisted on personal, relational, and pastoral care of every soul under one’s charge (see his book, The Reformed Pastor). The minister was the preacher, counsellor, teacher, advisor, advocate etc.

- Anglican tradition spoke of the “cure of souls” (or “care of souls”) probably best summed up in 1 Thessalonians 2:7-8. The apostle who taught, planted churches, instructed elders also was like a nursing mother, sharing his own life with brothers and sisters.

Throughout history, overlapping roles were normal and necessary in the church’s care. Indeed, who else was a person seeking help going to go to? There were no sources of secular help. Nor were there any Christian versions of it.

4. What Are the Benefits of Multiple Relationships?

Continuity and Trust (Family)

Being members of the household of God (Ephesians 2:19), brothers and sisters in Christ, should bring both continuity and trust to our biblical counselling relationships. These are relationships of permanence, obligation and familiarity. When our biblical counselling relationships are formed from within these pre-existing bonds there is inevitably some form of trust and shared history.2 The relationship doesn’t start at meeting one, nor finish at the end of the final session. Furthermore, it makes superficial or performative counselling much harder to sustain.

Accountability and Embodied Wisdom (Body)

Accountability is a key challenge within any relationship, especially those where there is unbalanced power. A counselling relationship that exists within the wider context of the gathered people of God and the structures for ordering his people that God has given us provides inherent accountability.

As living stones built together (1 Peter 2:5) and members of one body (1 Corinthians 12) we are neither autonomous nor isolated. The fruit of our counselling can be tested and witnessed amongst the church. For example, are those we are meeting with growing in godliness, peaceableness, gentleness, self-control, love for God and a love for others?

Integrated Counsel (Body and Temple)

Counselling that happens within the wider life of the church is part of the body of Christ building itself up in love (Ephesians 4:15-16). Where roles overlap, perhaps friend, counsellor, small group leader there is opportunity for care to be both broader and reinforced in different ways. This kind of integration guards against the compartmentalisation that sees the person we are seeking to help as a “case.” Rather it helps us see them as part of the body of Christ who we are walking alongside and seeking to serve.

Mutuality and Reciprocity (Body and Flock)

Every Christian relationship has an element mutuality. Even when we are primarily offering care, we are also being cared for. We are commanded to “bear one another’s burdens” (Galatians 6:2). And in the body, “the eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I have no need of you’” (1 Corinthians 12:21).

When biblical counselling happens in the context of other relationships this kind of mutuality and reciprocity is more natural and obvious. The counselee may pray for the counsellor during a small group meeting or provide a meal during a season, for example.

Credibility and Coherence (Family and Temple)

Paul repeatedly stresses how his ministry was embodied, relational and transparent. His words were supported by the life he lived, he showed what the gospel lived out looked like (e.g., 1 Thessalonians 2:1-12, Acts 20:18, Philippians 3:17). Multiple relationships allow the person being counselled to witness what a life lived for Jesus looks like through seasons of joy, struggle, trial and temptation. They can ask, does this person live what they teach? Are they the same in prayer, in parenting, in pain? This reinforces trust and helps develop integrity within the relationship.

5. What Are the Challenges?

Despite the benefits, multiple relationships bring complexities that become particularly acute when one of those relationships takes the form of counselling. The concerns raised within secular psychotherapy and counselling are legitimate. For example, we often wrestle with:

- Blurred roles – Who am I in this moment?

- Objectivity – Am I too close to speak hard truths?

- Dependency – Is there ongoing reliance or role confusion?

- Confidentiality – Especially where there’s shared community

- Conflict of interest – What happens when the priorities of different types of relationship seemingly come into conflict?

- Burnout – How do I continue to love someone well in multiple areas of life?

These concerns mirror warnings in Scripture about partiality, improper use of power, and neglecting limits (e.g. Jethro’s advice to Moses in Exodus 18:17-18; not pursuing dishonest gain or lording it over others, in 1 Peter 5:1–4; judging and preferential treatment in James 2:1–4; shepherds who feed on the flock in Ezekiel 34:1–10; the sin of elders in 1 Timothy 5:19–20.)

The problem lies not in the multiplicity of relationships, but in our sin-distorted use of the power they create. This issue isn’t specific to counselling relationships, but is particularly acute within them because they create a level of personal, spiritual and social vulnerability that is largely mitigated by more secular models. A biblical counselling relationship adds a knowledge and power imbalance that is more akin to part of the pastor/ elder role. But where we also have other types of relationship we tend not to notice these characteristics. We don’t feel as if we have power, so we don’t keep as close a watch on our lives and what we’re saying as we should. The fact that a biblical counselling role creates an imbalance somewhat like the pastor/ elder role is useful, because it means we can pick up on some of the recent material on this topic and let this help us think through how we might wisely care well for ourselves and others.

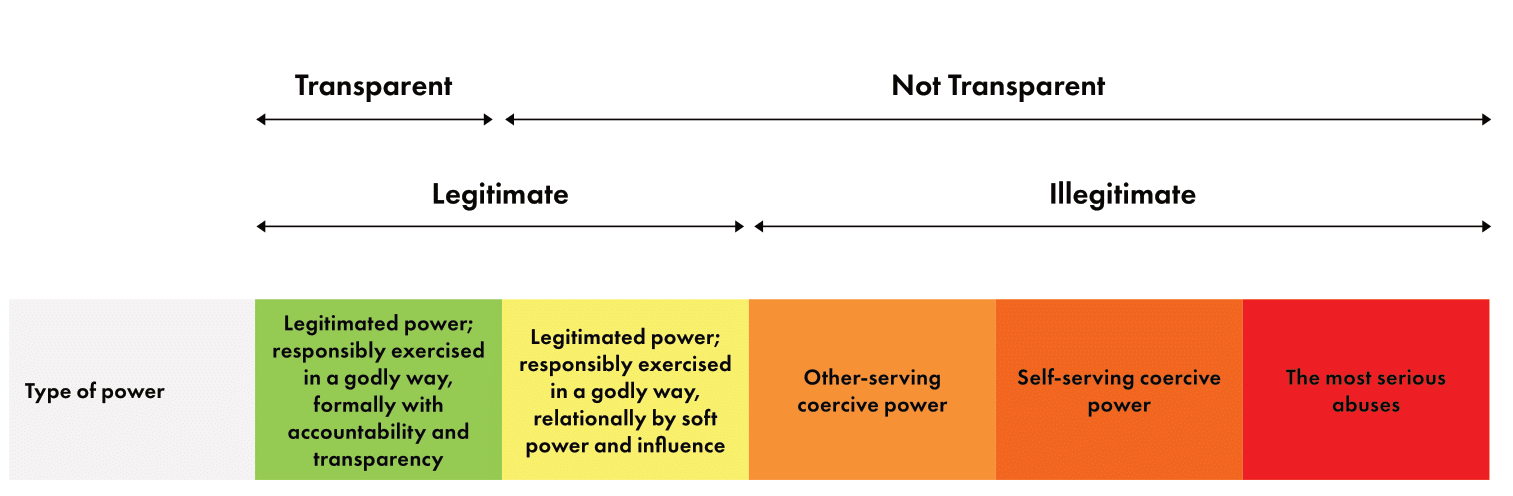

In his book ‘Powerful Leaders?’ Marcus Honeysett uses this diagram which may be helpful to us:3

The secular model does everything it can to stay in the green box, aside from perhaps slightly limited transparency (most counselling happens one-to-one without direct oversight). The power is exercised in what is understood to be an ethical rather than godly way. Formal intake processes are followed, there is clear supervision in place. Avoiding other forms of relationships means that any soft power and influence is minimized.

The multiple relationships we have in Christian and church circles means that many of us operate primarily in the yellow box. There aren’t the same formalized structures in place, and lines of accountability often aren’t that clear (because they don’t exist as naturally in a flock or amongst brothers and sisters). Counselling often emerges out of other less formal relational structures. We work with a high degree of soft, relational power, rather than structural power.

That makes what we do more risky because it’s easier to slide into the illegitimate use of power.

The light orange box describes those situations where we are using the power we have - perhaps the knowledge we have, or the influence - for the good of others, but in an illegitimate way. Perhaps we try and protect people from making mistakes by taking their agency away in some way. We are trying to act for their good, but in a way we have no authority or right to do.

The darker orange box is a shift to using power for our own ends. Perhaps we use the relationship we have to enhance our reputation or bring about changes in church we might want.

The red box is the most serious end, where we use what we know for our own gain, maybe our own advancement. This involves the worst expressions our own sinful desires with high levels of control, domination and exploitation.

6. What Might This Mean in Practice?

In General

What things can we be doing, or should we be doing to engage in biblical counselling whilst:

- Enjoying and building on the multiple relationships God has ordained for us to have in the church?

- Recognising the inherent risks that power brings when it meets our own and others sinfulness?

- How do we seek to stay in the green and yellow boxes without sacrificing who God has called us to be?

- Are there ways this thinking should influence our informal interpersonal ministry? In what ways does the risk change (both to a lesser or greater extent) in more formal contexts?

- What structures of supervision or mutual accountability could be introduced without undermining the relational closeness?

In Particular

Here is my situation with Anna again:

“I’ve known Anna for about a decade, initially as a small group member, then a friend, now as friend and pastor. We have walked a long road together wrestling, amongst other things, with singleness, long term suffering, sexual assault and miscarriages. We’ve also rejoiced over healing, marriage, Christian growth and God’s faithfulness. We have lived in the same house for a while, been on holiday once as families together. Finally, I also met with Anna to do some biblical counselling for almost a year….”

- What are the multiple relationships at play here?

- How do they influence the power dynamics present?

- What might sliding through the orange boxes toward red box actually look like? What should we be on the alert for?

6. Conclusion

Secular psychotherapy and counselling have developed extensive ethical guidelines to seek to mitigate the risks inherent in the practice. These are founded on a particular understanding of the relationship between the counsellor and counselee. A biblical foundation of interpersonal relationships between Christians is largely incompatible with the medical model of care and biblical counselling practices that use it as a starting point are likely to always struggle to reconcile the two. There is a need to develop both good practice and awareness of relational dynamics at the informal end of the conversational ministry and practical ethical guidelines to govern the more formal side, both rooted in the relationships we share in Christ.

Appendix

APA Ethics

3.05 Multiple Relationships

(a) A multiple relationship occurs when a psychologist is in a professional role with a person and (1) at the same time is in another role with the same person, (2) at the same time is in a relationship with a person closely associated with or related to the person with whom the psychologist has the professional relationship, or (3) promises to enter into another relationship in the future with the person or a person closely associated with or related to the person.

A psychologist refrains from entering into a multiple relationship if the multiple relationship could reasonably be expected to impair the psychologist’s objectivity, competence, or effectiveness in performing his or her functions as a psychologist, or otherwise risks exploitation or harm to the person with whom the professional relationship exists.

Multiple relationships that would not reasonably be expected to cause impairment or risk exploitation or harm are not unethical.

BACP Ethics

- We will establish and maintain appropriate professional and personal boundaries in our relationships with clients by ensuring that:

a. these boundaries are consistent with the aims of working together and beneficial to the client b. any dual or multiple relationships will be avoided where the risks of harm to the client outweigh any benefits to the client c. reasonable care is taken to separate and maintain a distinction between our personal and professional presence on social media where this could result in harmful dual relationships with clients d. the impact of any dual or multiple relationships will be periodically reviewed in supervision and discussed with clients when appropriate. They may also be discussed with any colleagues or managers in order to enhance the integrity of the work being undertaken.

ACA Ethics

A.5.d. Friends or Family Members Counselors are prohibited from engaging in counseling relationships with friends or family members with whom they have an inability to remain objective.

A.5.e. Personal Virtual Relationships With Current Clients Counselors are prohibited from engaging in a personal virtual relationship with individuals with whom they have a current counseling relationship (e.g., through social and other media).

A.6. Managing and Maintaining Boundaries and Professional Relationships A.6.a. Previous Relationships Counselors consider the risks and benefits of accepting as clients those with whom they have had a previous relationship. These potential clients may include individuals with whom the counselor has had a casual, distant, or past relationship. Examples include mutual or past membership in a professional association, organization, or community. When counselors accept these clients, they take appropriate professional precautions such as informed consent, consultation, supervision, and documentation to ensure that judgment is not impaired and no exploitation occurs.

A.6.b. Extending Counseling Boundaries Counselors consider the risks and benefits of extending current counseling relationships beyond conventional parameters. Examples include attending a client’s formal ceremony (e.g., a wedding/commitment ceremony or graduation), purchasing a service or product provided by a client (excepting unrestricted bartering), and visiting a client’s ill family member in the hospital. In extending these boundaries, counselors take appropriate professional precautions such as informed consent, consultation, supervision, and documentation to ensure that judgment is not impaired and no harm occurs.

-

Shrier, A. (2024). Bad therapy: Why the kids aren’t growing up. Swift Press, 73. ↩︎

-

Even where we don’t share a personal history, we share a history as the people of God. In the same way the Passover was instituted, in part, to provide a shared history for God’s people, so to does communion in the context of the new covenant. ↩︎

-

Honeysett, M. (2022). Powerful leaders?: When church leadership goes wrong and how to prevent it. IVP, 37. ↩︎